By Hindustan Times

A selection of photographs of the 2,000-year-old art in India’s Ajanta caves has been deposited in the Arctic World Archive. Meet the Indians who made that happen.

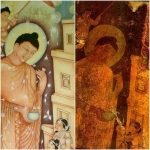

It’s been 2,000 years since unknown artists created the paintings on the walls of the Ajanta caves in the Sahyadri Mountains of western India. The paintings are considered the greatest examples of Buddhist art, and the inspiration for schools of Buddhist art that would emerge across Asia in the centuries to come.

Now, they’re being preserved — or at least images of them are — in the Arctic World Archive (AWA), a depository meant to safeguard elements of human civilisation in case of an apocalyptic event.

In October, seven high-resolution photographs of the paintings were deposited in the AWA, a storage facility situated deep within a mountain midway between Norway and the North Pole, on a remote island in the Svalbard archipelago. The images have been copied onto 35mm photosensitive film with an estimated shelf life of over 1,000 years.

This is the second deposit of Indian origin in the vault; the first was a A digital copy of 18 chapters (700 shlokas) of the Bhagavad Gita in Sanskrit, Hindi and English, made in 2018.

Like its neighbour the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, the AWA is being designed to withstand a range of natural disasters, explosions and even potentially nuclear blasts.

“Theft is near impossible, and getting the medium online is a guarded process accessible only to the depositors,” says Patricia Alfheim, a communications manager for Piql, the company that owns the vault.

The depositors, in this case, are Sapio Analytics, an advisory firm whose heritage division initiated the project. Over the next few years, all 31 of the rock-cut Buddhist caves (created between the 1st century BCE and 5th century CE) will be digitally mapped, restored and the data archived in the AWA.

““We are making a 3D map of the caves with minute detail using a proprietary AI restoration algorithm as well as the expertise of manual restorers such as artists and art historians,” says CEO Ashwin Shrivastava. “We picked these caves because they are a gateway to an ancient culture.”

No one understands this better than art historian and photographer Benoy K Behl, who shone a proverbial light on the caves back in 1992. Behl is credited with producing some of the earliest photographs of the Ajanta paintings, one of which is among those now preserved in the vault.

Back then, all he had to work with was 100 ASA Ektachrome film, a third-generation Nikon camera and a passion for long exposure and lowlight photography. These he needed to shoot inside the caves, where artificial light and camera flashes are not permitted. Capturing their true colours was the hardest part, he remembers.

The image selected from that series is of the 5th century painting of King Mahajanaka. It’s being preserved along with his paper, Revelation of Ajanta & Ancient Indian Mural Paintings.

“The marvellous thing about the painting is the inward look in the eyes. It is a running theme in ancient art, to transport us from the noise and glamours of the material world around us to a peace that can be found within,” says Behl. His is the only photograph in the series that was shot on a manual camera, all the others were shot later, on digital cameras but as the paintings fade with time and exposure within the caves, his remain some of the most precious.

For Behl, who has spent decades advocating the importance of the art at Ajanta, seeking to protect, preserve and restore this art is a step in the right direction. What we seem to have sidestepped in the past, could perhaps be given its due in the future, he says.

“There is a huge commercial infrastructure in the world of history that focuses on what is sellable and previously held knowledge tends to keep propagating itself,” he says. “The Ajanta caves for some reason don’t feature in that.”

Add Comment