By Gowri S News Courtesy: The Hindu

Art historian Benoy K Behl’s 1992 photograph of a painting in the Ajanta Caves has been preserved in the Arctic World Archive

King Mahajanaka looks inward in deep reflection as he renounces his princely possessions and worldly life. He rides out of the palace to become an ascetic, his line of sight suggesting that he is withdrawn. This particular painting, which resides in Cave 1 of the Ajanta Caves, represents everything that the famed ancient art is hailed for: details and narrative quality.

Delhi-based art historian and filmmaker Benoy K Behl’s photograph of this painting (taken in 1992) has now been preserved for posterity in the Arctic World Archive by Sapio Analytica in Svalbard, Norway. It will be preserved in a steel vault on an island located 970 kilometres from the North Pole.

Behl began documenting arts and culture as early as 1976. His interest, even as a child, was always pointed at history. “In fact, in school we had this little history book for study. Instead of that, I picked up a huge book called The Advanced History of India and spent hours at Lodhi Gardens studying it,” he recalls.

Even within history, Asia’s Buddhist art is a specific strain that Behl specialises on. “When you start looking at the remaining heritage in India, a large part of it is obviously Buddhist art. So, I found myself drawn towards it automatically.”

In 1991 and 1992, his experience at the Ajanta Caves, documenting the ancient art inscribed on the caves using zero-light photography, led to a transformation in him. The paintings at Ajanta, till then, had never been photographed and the technical challenges were aplenty owing to the lack of light. “In 1990, I had developed a technique of photographing in extremely-low light conditions,” he says. So, this project presented him with the opportunity to experiment with the technique. “

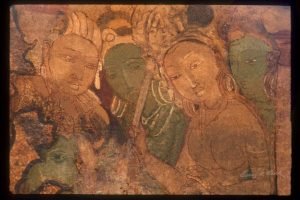

“The many weeks that I spent in Ajanta were finally much more meaningful than just the technical challenge,” recalls Behl, adding, “I was given a full, long exposure to the grace and compassion contained in Indian art.” Each of the many thousands of painted figures at Ajanta oozes compassion and kindness towards others, adds Behl. “And, if you spend enough time with them, you can’t help but be transformed.”

Jogging his memory of the time he spent at the caves, Behl, who worked under close supervision of ASI while on the project, narrates, “There was a watchman named Chintamani and he had been working in the cave for nobody knows how long. And, he was kind of a gruff man. So, on the first day, I began my work on Cave 26 at the far end of the Ajanta and was setting up the equipment. And, Chintamani walks up to me and says, ‘Yeh photography kuch alag cheez hone wali hai (This photography is going to be different).’”

And so it did. Behl’s 1,000 or more photographs of the Ajanta paintings dated between 2nd Century BC and 5th Century AD, had garnered global attention for documenting and preserving a prominent chapter of India’s rich ancient art. Explaining how detailed these paintings are, Behl continues, “In the pearl strings that dangle on a woman’s bosom, one can see even the curvature of those pearls, that suggests movement.”

In terms of the quality; the emotion it evokes and technical virtuosity, it stands apart, which is why Behl believes that it is an important step for Indian art history that the photograph has been preserved.

Add Comment